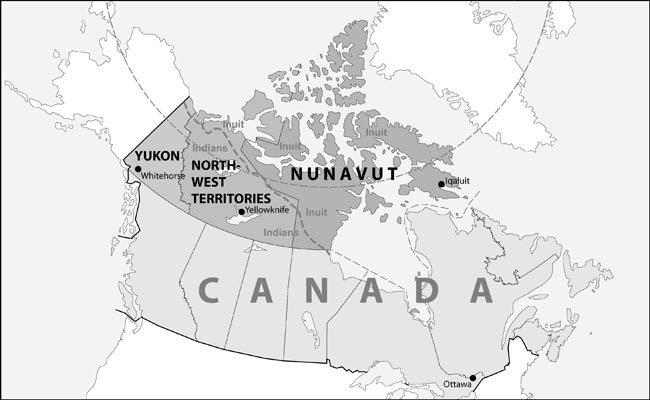

The three territories of Northern Canada

Robert M. Bone, published in The Canadian North: Embracing Change, CRIC Paper (June 2002), with some modifications and map by Winfried K. Dallmann

Canada north of the 60th parallel is the least known and least populated part of the country. Yet it looms large in the national psyche. The “Territorial North” – which includes Yukon, the Northwest Territories (NWT) and Nunavut – helps define the country, both to its citizens and the world, as one with a wilderness tradition. No less than 88% of Canadians say that the Canadian North is important to their sense of national identity.

Although most Canadians cherish the North, only a few have seen the area that accounts for nearly 40% of the country’s surface, covering over 3.9 million km2 of forest, tundra, rivers, lakes and salt water. Within its bounds live fewer than 100,000 people – 0.3% of Canada’s population.

Few southern Canadians may be aware that almost half the region’s population is Aboriginal (48.4% in 1996), and that these residents consider the North not as “wilderness” but as their homeland. As a consequence, the Territories are the site of major modern land claims and self-government negotiations and agreements. In 1984, the Inuvialuit Final Agreement marked the beginning of a series of land claims agreements in the Territorial North.

Nunavut is a product of such an agreement and is unique among Canadian territories and provinces because the vast majority (ca. 83%) of its people is Aboriginal. The NWT's population is approximately 50% Aboriginal, while Yukon's is only 21%.

YUKON

Much of the Yukon Territory is mountainous. The majority of people live in the river valleys of the Yukon Plateau. Most settlements, including Whitehorse, are found near the Yukon River, the fifth-longest in North America. In fact, Yukon is derived from the Gwich’in language, meaning ‘great river’.

The population is nearly 30,000. The vast majority (79%, in 1996) are non-Aboriginal Canadians, attracted by high wages. Most usually plan to stay only a few years. When the territorial economy slows, many non-Aboriginal Yukoners move south. This type of movement explains the recent decline in the Territory’s population — it fell by 6.8 % between 1996 and 2001. One contributing factor was the 1998 closure of the Faro lead and zinc mine.

Whitehorse, the largest city in the three territories, is Yukon’s capital, and its transportation, business, and service center. Until the construction of the Alaska Highway (1947), the Yukon River was the main transportation route between Whitehorse and Dawson.

In 1896, the Klondike gold rush brought in thousands of outsiders, thereby transforming the territory and swamping the local Indian population. In 1898, Yukon became a separate territory with Dawson as its capital. However, the subsequent demise of the placer gold deposits spurred a massive out-migration and the population declined dramatically.

The Klondike gold rush brought many Americans and other foreigners to this part of Canada’s North. Ottawa realized that an expression of Canadian sovereignty was necessary and, in 1898, it acted by appointing a commissioner and several members to form a governing body. Yukoners, however, were not satisfied with Ottawa’s ‘colonial’ arrangement and they demanded elections. By 1908, Yukon had an elected council of ten members. However, with the drop in Yukon’s population, the elected council was downsized.

During World War II, the Yukon’s population began to increase as a result of military activities. These included the construction of the Alaska Highway and the Canol Pipeline from Norman Wells to Whitehorse. The population continued to increase due to economic development resulting from improved access afforded by the Alaska Highway, high world prices for metals, and an expanded role for the Yukon government, which resulted in the hiring of many more public employees. After World War II, the number of council members increased to match Yukon’s growing population. Unlike the other territories, which have governing bodies based on “consensus” government, traditional party politics are the rule in Yukon. The Yukon Legislative Assembly has 17 elected members.

Most of Yukon’s Aboriginal population live in smaller settlements. In 1993, the Yukon First Nations were successful in negotiating the Umbrella Final Agreement between the Government of Canada, the Council for Yukon Indians and the Government of the Yukon that led to a series of land claims agreements with Yukon First Nations.

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (NWT)

The Northwest Territories originally covered the huge geographic area acquired in 1870 from the Hudson’s Bay Company. Over the years, new provinces and territories were carved out of the NWT, and Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec were also enlarged at its expense. The NWT now covers 1.3 million km2, making it the second largest political unit in Canada.

In 2001, the NWT’s population was 37,360, a 5.8% decrease since 1996, resulting from out-migration promted by an economic downturn in the late 1990s.

Yellowknife, on the north shore of Great Slave Lake, was chosen as the NWT’s capital in 1967. With a population of 16,541 in 2001, it is the second largest city in the three territories. Originally a gold mining town, Yellowknife blossomed into a modern and diversified city after it became the capital. In the late 1990s, spin-offs from the construction of the Ekati diamond mine, located 320 km northeast of Yellowknife, gave the city new economic life. Now two more diamonds mines (Diavik and Snap Lake) are on stream and should begin production within two years. An agreement with these companies ensures that a portion of the diamonds are sorted, evaluated, cut and polished in Yellowknife, making it North American’s premier diamond-processing center.

The next largest communities are Hay River (3,510), Inuvik (2,894), and Fort Smith (2,185). The populations of the remaining 28 communities range from 70 to 1,552.

Modern land claims negotiations have played a key role in the NWT’s evolution. In 1984, the first comprehensive land claims agreement in Canada was the Inuvialuit Final Agreement between Ottawa and the Inuvialuit (Inuit indigenous to the Western Canadian Arctic). It set the stage for three more agreements in the NWT: the Gwich’in Final Agreement 1992, the Sahtu/Metis Final Agreement 1993, and the Nunavut Final Agreement 1993, leaving the Deh Cho (South Slavey) without a land claims agreement.

The Legislative Assembly of the NWT has 19 members, and while it works much like a provincial legislature, there are no political parties. Each member votes according to his or her conscience on any matter. The members of the Executive Council, or cabinet — six ministers and a premier — are elected by the members of the Assembly.

NUNAVUT

In 1976, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (national voice for the Inuit of Canada, recently renamed itself Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami) proposed creating an Arctic territory called Nunavut that would represent the political interests of Canada’s Inuit. It took nearly 25 years, but on April 1, 1999, Nunavut — ‘our land’ in the Inuktitut language — was formed out of the eastern part of the Northwest Territories.

Nunavut is the largest territory, by far, covering over 2 million km2. Most Canadian Arctic islands (which include some of the largest in the world) are part of Nunavut.

At the same time, Nunavut has the smallest territorial population (26,745 inhabitants). Nunavut’s population is growing rapidly (at an annual rate of 1.6%) due to its high birth rate. Its people are scattered across the tundra in small, isolated settlements. Unlike the other two territories, Nunavut does not have highways that connect its main settlements. The other distinguishing demographic feature of the Territory is the fact that its population is 85% Inuit.

Iqaluit, on Baffin Island, is the capital and the third largest municipality in the Territorial North with a population of 5,236. The next largest communities in Nunavut are: Rankin Inlet (2,177), Arviat (1,899) and Cambridge Bay (1,309). Most remaining communities have fewer than 1,000 inhabitants.

Nunavut’s creation followed the conclusion in 1993 of a comprehensive land claims agreement between the government of Canada and the region’s Inuit people. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement called for a cash settlement of $1.1 billion to be paid to the Inuit in annual installments until 2007, and title to 358,000 km2 or 18% of the land area of Nunavut.

Most importantly, the Nunavut agreement recognized the Inuit’s aspirations for a territorial homeland and thereby set the stage for the establishment of the Territory of Nunavut. While all residents of Nunavut have equal rights, the demographic reality is that 85 of every 100 of its inhabitants are Inuit, making the territory a vehicle through which their political aspirations can be expressed. Demography and politics have forged Nunavut into a unique political entity within Canada. Territorial government policies and programs reflect Inuit aspirations, beliefs, and values. Two examples of this are: (a) the principle of decentralization that ensures that government is close to the people; and (b) the principle of promoting of the Inuktitut language and culture.

The Legislative Assembly has 19 members. There are no political parties. The Premier and Ministers are elected by the Assembly to form the Executive Council or Cabinet.

Appendix (W. Dallmann)

Indigenous peoples of Yukon:

Indian tribes (all belonging to the Dene Nation): Gwich’in, Hän, Tagish, Tutchone, Tlingit

Indigenous peoples of the NWT:

Indian tribes (all belonging to the Dene Nation): Gwich’in, Kaska, Yellowknife, Dogrib, Bear Lake, Sahtu (North Slavey),

Deh Cho (South Slavey), Chipewyan

Inuvialuit (Inuit group)

Indigenous peoples of Nunavut:

Inuit

| Territory |

area in km2; |

population (2001) |

percentage change |

percentage population of Canadian total (2001)

|

aboriginal population |

percentage of total aboriginal population |

largest settlements, population (2001) |

|

Yukon |

382,443 (3.8%) |

28,674 |

-6.8% |

0.09% |

20.2% |

Inuit - 0.4 |

Whitehorse - 19,058 |

|

Northwest Territories (NWT) |

1,346,106 (13.5%) |

37,360 |

-5.8% |

0.12% |

48.2% |

Inuit - 15 |

Yellowknife - 16,541 |

|

Nunavut |

2,093,190 (21%) |

26,745 |

+8.1% |

0.08% |

83.4% |

Inuit - 89 |

Iqaluit - 5,236 |

|

total |

3,921,739 |

92,779 |

-2.5% |

0.29% |

48.4% |

|

|

Agreements between governments and indigenous peoples in Canada

compiled by W.. Dallmann

There are 44 self-government agreements, 47 comprehensive land-claims agreements, 1 land governance agreement. Complete agreement texts are provided on the website http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/agr/index_e.html. The five agreements mentioned in the article by Robert M. Bone (see above) are briefly described below.

Inuvialuit Final Agreement (NWT)

Approved 1984

http://www.taiga.net/wmac/ifa/

The basic goals of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA), as expressed by the Inuvialuit and recognized by Canada, are to preserve Inuvialuit cultural identity and values within a changing northern society, enable Inuvialuit to be equal and meaningful participants in the northern and national economy and society and protect and preserve the Arctic wildlife, environment and biological productivity.

Approved by the Parliament of Canada in 1984 as the Western Arctic Claims Settlement Act, the IFA takes precedence over other acts inconsistent with it. This Act is also protected under the Canadian Constitution in that it cannot be changed by Parliament without approval of the Inuvialuit.

The IFA provided financial compensation and ownership of 91,000 square kilometres (35,000 square miles) of land including 13,000 square kilometres (5,000 square miles) with subsurface rights to oil, gas and minerals.

Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (NWT/Yukon, Final Agreement)

Approved 1992

http://www.gwichin.nt.ca/landClaimAgreement.htm

Under the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, the Gwich’in Tribal Council (GTC) was granted ownership of 16,264 square kilometres of land in parcels located throughout the Gwich’in Settlement Area and the Yukon. The GTC is responsible for administering these lands and managing the resources connected with them for the benefit of all Gwich’in beneficiaries. This means balancing the need to conserve natural resources with development that can provide the basis for future economic growth and independence.

Umbrella Final Agreement (Yukon)

Approved 1993

http://www.cyfn.ca/ouragreementsufa?noCache=826%3B1105787378

The Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA) is an overall 'umbrella' agreement of the Yukon Land Claims package and provides for the general agreement made by the three parties (Government of Canada, Yukon Territory, Council for Yukon Indians) in a number of areas. While the agreement is not a legal document, it represents a 'political' agreement made between the three parties. The Umbrella Final Agreement contains several main topics from which all of the remaining topics flow. These include land, compensation moneys, self-government, and the establishment of boards and committees and tribunals to ensure the joint management of a number of specific areas.

While the Umbrella Final Agreement provides a framework within which each of the 14 Yukon First Nations conclude a final claim settlement agreement, all UFA provisions are a part of each First Nation Final Agreement (FNFA). The Final Agreements contain all of the text of the Umbrella Final Agreement with the addition of specific provisions which apply to the individual First Nation.

Sahtú Dene Metis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (NWT, Final Agreement)

Approved 1993

http://www.sahtu.ca/sahtulc.html

http://www.sahtu.ca/pdf/sahtulc/readmore-slc.pdf

The agreement provides the Sahtú Dene and Metis with title to 41,437 sq. km of land in the Northwest Territories. Subsurface rights are included on 1,813 square kilometres of this land. In addition, the Sahtú Dene and Metis will, over a 15 year period, receive financial payments of $75 million (in 1990 Canadian dollars) and share the resource royalties paid to governments each year in the Mackenzie Valley.

Nunavut Final Agreement

Approved 1993

http://www.tunngavik.com/site-eng/nlca/nlca.htm

http://www.tunngavik.com/site-eng/engmain.html